Interviews

Knowing the Score: The wise man of movie music composition, Elmer Bernstein, celebrates 50 years in Hollywood

Interview by Roger Friedman | Red Carpet – Oscars

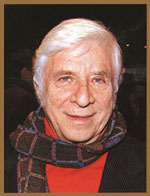

Bernstein at the November 2002 Far From Heavenpremiere at the Beekman Theatre in New York. Photo by Bud Gray/MPTV.NET

Elmer Bernstein is 80 years old and has won one Academy Award for his 13 nominations. A student of the immortal Aaron Copland, Bernstein’s music is marked by tremendous melodies and lush orchestrations. But his sound is never saccharine and his best soundtracks – like Far From Heaven, The Magnificent Seven, and To Kill a Mockingbird – are symphonies on their own.

RED CARPET: Who are your contemporaries?

ELMER BERNSTEIN: I don’t have any! They’re all younger. John Williams, Jerry Goldsmith. But they’re my gang. John Barry is also younger than I am.

RC: What do you think of the next generation?

EB: My favorite is Thomas Newman. His father is Alfred Newman. James Newton Howard is very, very good. Rachel Portman has a nice voice.

RC: Far From Heaven really has the feeling of the ’50s to it.

EB: For me, I was doing what I thought the film needed. That’s what the characters needed. It’s honest, it’s not synthetic.

RC: How different is it doing Far From Heaven than To Kill a Mockingbird?

EB: They were really friendly collaborations. All you’re concerned with is what’s the right note. If that can be done without ego, you’re OK. With Mockingbird, I’d read the book. The difference is [director Robert] Mulligan and I were old friends before we even shot a frame. With Todd Haynes, he had virtually finished the film before I saw it. I thought it was so interesting. All I knew was he was half my age, [and] I’d better find out about this guy. So I went to the store and ran all his films. Poison, Safe, Velvet Goldmine. I thought, “Well, he’s a risk-taker!” Far From Heaven was a very risky film to make. I like Safe. I think it’s a very interesting film. I told Julianne [Moore] you could use Safe and Far From Heaven as bookends.

RC: Did you know the films of Douglas Sirk?

EB: No. In those days, in the ’50s, I was on the other cutting edge. I was doing The Man With the Golden Arm, Sweet Smell of Success, a total other direction. I never saw Sirk’s films.

RC: You don’t remember him at all?

EB: It was a different world for me. I only did one of those kinds of movies – weepies – in the ’50s. It was called The View from Pompey’s Head, which was that kind of romantic film. But I didn’t know Douglas Sirk’s work.

RC: Sweet Smell of Success is my favorite movie.

EB: It’s a brilliant film. It’s hard-edged and it doesn’t give a quarter anywhere.

RC: Did you work with Ernest Lehman [writer, Sweet Smell of Success]?

EB: This is a crazy thing, but in that period of time, composers didn’t work with the director. Harold Hecht [executive director] brought me in. Two years before, I’d done Golden Arm, and I was [of] that sensibility. You were the composer and they generally assumed you knew what you were doing.

RC: Did you know Sweet Smell would be such a big deal?

EB: I knew with Golden Arm and the jazz score [that] it was unusual. I figured I [had] better talk to Otto Preminger [director]. I said, “I have an idea I want to run by you. I’d like to have a jazz orchestra with a symphonic orchestra.” He said, “If that’s what you think you want to do.” And that was very unusual for Otto. After two weeks, he’d say, “What’s it going to sound like?” So we made a disc for him. In Sweet Smell… when I look at a film, I don’t judge it. I say, “This is the task. This is my job. What do I do?” If this film’s hateful, I wouldn’t do it.

RC: Such as?

EB: There were certainly films I didn’t do for political reasons. I did a lot of films for John Wayne, but I wouldn’t do [The] Green Berets.

RC: You worked with Wayne on The Shootist, though…

EB: Well, Don Siegel [director, The Shootist] was the real thing. But Wayne was very ill and it was hard for him. Ron Howard was the young boy.

RC: You did Al Pacino’s Chinese Coffee? It’s never been released.

EB: Al had problems with it. I was the second scorer on it. Howard Shore did it first. If you’re replacing work by Howard Shore, I wouldn’t do it.

RC: What’s the movie like?

EB: It’s a conversation piece between [Al] and Jerry Orbach. It’s a really interesting film about the artistic endeavor. Because it comes from a play, it is static. He loved the score. But he never wanted to do anything further. That was two, three years ago. I don’t think Al intends for it to be released. It was fun doing the work. I thought we had it made.

RC: You’ve done a lot with Martin Scorcese. Did you do Gangs of New York?

EB: The story is really complex. I’ve done about seven films with Scorcese. On Gangs of New York, Marty could never quite make up his mind about what he wanted. Then, he got into this long, painful edit. I wrote way back, nine months ago, some music for the film. I went over it with him. But as he went along, he began to have some other concept of what he wanted. He winds up with a Scorcese score, a pastiche. My understanding is Howard [Shore] had a piece of concert music and they did something with it.

RC: So how much did you write?

EB: A complete score. This isn’t the moment, but in a [few] months, I might ask for permission to put it on a record.

RC: Of all the Scorcese movies, which is your favorite?

EB: [The] Age of Innocence. We talked about everything on that one, bounced ideas off each other. I was doing a lot of stuff while he was editing and we were in contact all the time.

RC: Your music is very lush and his films are edgy. How did that work in Gangs?

EB: It was pretty violent music. No violins. All brass and woodwind, very different. But I think Marty, all the time he was working on the film, had a great reliance on Irish street music, folk music. I think he probably wanted to keep it very folksy somehow.

RC: Sometimes you made three movies a year…

EB: You figure that your general involvement with a film is three months. So you can do three films.

RC: You also had a comedy period.

EB: It started with Animal House. Then there’s Stripes, Heavy Metal, Caddyshack. It went on for 10 years. Airplane!. That one’s hysterical. John Landis, who directed Animal House, is a childhood friend of my son. He asked me to do it. He had a great idea, to score it like it’s a drama without comedy music. And the effect was very funny.

RC: You did The Shootist the year before Animal House.

EB: That was not a comedy! But it got to the point with Ghostbusters that I knew I had to leave comedy.

RC: Do you think Aaron Copland was rolling in his grave?

EB: He’s O.K.! But he was the first person who ever heard me play the piano. I was 12 years old and he wasn’t such a big star then. My piano teacher took me to see him. I played this little piece for him. He wound up giving me lessons. You do hear him in To Kill a Mockingbird and in The Magnificent Seven. It’s sort of a foursquare, a very American kind of thing.

RC: Is it conscious on your part?

EB: It’s hard to say what’s conscious anymore. You just absorb all this stuff.

RC: Do you ever have trouble with directors helping them with their vision?

EB: On Keeping the Faith, Edward Norton had a lot of trouble getting a particular piece near the end of the film right. He had never directed before and had trouble communicating what he wanted. But he’s a bright, bright man. I wish he would direct again.

RC: What’s the future of movie scores?

EB: Oy! Once the motion picture companies realized [that] there was money to be made just from songs, there was trouble. But the problem is the films, not the composers.

RC: What do you think is your most recognizable piece of music?

EB: I’ll tell you a story. I was in Spain last year doing some concerts near Barcelona. We were in this tiny town. I sat down at a little sidewalk café. There was a mechanical horse that kids like to ride, you put a quarter in. All of the sudden it starts to play The Magnificent Seven! I thought, “Now I know what my life has been about!”