Memorials

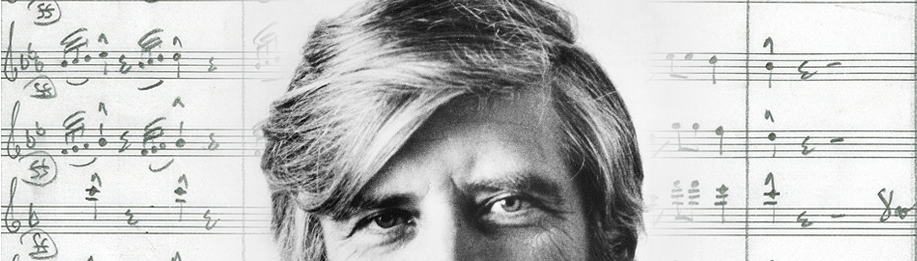

Greg Bernstein on Elmer Bernstein

Partial Transcript of Memorial Speech

Greg Bernstein

There were so many things that were so wonderfully him. I don’t know why—maybe an analyst would have to tell me—but when I’ve thought about my father in the past few weeks, my mind has gone to those moments when my father was showing his…dislike…for authority figures. He did not like being told what to do…for example…being ordered to pull over for speeding. I remember once, early in the morning, leaving with him in his brand new Ford Cobra sports car—he did love cars—to drive down to Palm Springs. We were on Laurel Canyon, which was deserted, when a police car…way, way behind us…turned on its lights and siren. My father just hit the gas, made a turn, and lost the officer somewhere near Art’s Delicatessen.

And not all authority figures needed to be human. There was the time he tried to train a donkey he had bought named Gabriel. Gabriel was a stereotypically stubborn donkey, and he did not want a human being on his back—but my father was not going to let the laws of nature …the authority of nature…prevail. So, my father sat on that donkey, which itself just sat down and refused to budge. I still have this image of my father, staring up at the sky as Gabriel sat…my father positioned like an astronaut before launch…demanding, ordering, Gabriel to move.

What strikes me is, even when training wayward donkeys, my father was confident he would succeed. I’m sure this confidence was helped by his fearlessness, for I really don’t believe he was much afraid of anything. I remember, after I quit legal work in 1988 and entered the AFI in an attempt to write and direct movies, I had a chat with him. I asked him if he was scared when DeMille handed him The Ten Commandments. He said he wasn’t scared at all. He said he had never been scared about his work…ever…and I think he meant it. I just don’t think he ever thought about failing, and I’m pretty sure that, on August 18th of this year, no one was more surprised by the fact he died than he. I’ve often been asked if my father was a tough act to follow. I always say “Yes,” but it wasn’t so much his talent that made him so—it was his confidence and his fearlessness.

I’m sure his sense of certainty was helped by his overwhelming passion. He felt things so strongly. He laughed hard. I have a very vivid memory of him and me walking in Hollywood in 1965, and on the spur of the moment on this hot summer weekend afternoon, we walked into a movie theater where a film called The Great Race was playing. And I remember him laughing really hard—we had a great day. Of course, he could be equally passionate about things that didn’t quite go his way. Like anything mechanical that failed. For those of you who saw him around a misbehaving machine, you know precisely what I mean. Of course, he was passionate about music. I can remember him playing the piano at home, playing with such energy, such force, such strength, that to me it seemed that the piano would break. And I remember falling asleep at night…I was lucky, his studio was next to my bedroom…and so I can remember To Kill A Mockingbird and other pieces filtering into my bedroom as I fell asleep. Those are very nice memories to have.

I would add that my father was passionate about a lot of different things, and for me this was great. He didn’t think only about music. He read about so many different things, and so he could teach me about sports, politics, about American history—he knew a lot about American history—about Irish history, English history, French history, the lives of composers, of scientists, novelists, Freud, horses, dogs, a million things. He learned about so much in his life…and he made learning something I wanted to do…for which I will always be grateful.

All the working…and the reading…the non-stop traveling…the boats…and ranches…the animals…the social functions…all his passion and determination…it all adds up to a life force that is hard to imagine gone. Less than a week after having cancer surgery, he flew to Seattle and piloted his boat through Puget Sound. Just a few weeks after completing radiation, he flew to Europe and conducted an orchestra….and he came by Boston, where I was, to see me and my family, and I had a chance to be next to him, which was nice. I suppose I will always be my father’s son, and so I will always remember best those times when I was next to him. Being right there next to him…it felt so safe…it was so much fun. In the early 60s, when I stood next to him on a dozen scoring stage podiums, shy but thrilled to be there; in 1963, when I sat next to him at the World Series, when his beloved Dodgers beat the hated Yankees; in 1964, when I stood next to him at a rally for President Johnson—he wanted me to see the President; in 1965, when I sat next to him at the Academy Awards on a terrible night for him—he had been nominated three times, and he just knew he would win once or twice, because he didn’t win for To Kill a Mockingbird, or The Magnificent Seven, or all the rest…and he won nothing that night, but I was next to him; I sat next to him on the plane that took me away to college, and I stood next to him some months later when he visited me on what turned out to be “National Streak Day”—streaking in 1974 became a fad—and there we stood together on a cold January night, on a street that had been barricaded off, and we watched together as floats came down the street every few minutes accompanied by naked people streaking…and we stood there for 15 minutes or so until we realized there were no girls streaking, and so we left.

Sadly, as I got older, my chances to stand next to him dwindled, and I regret this. But I will always be next to him, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.