Memorials

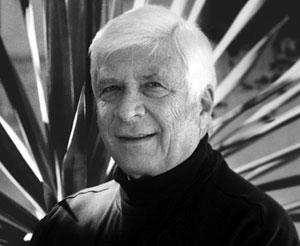

Tribute: Elmer Bernstein Remembered

Hundreds attend memorial tribute to dearly loved composer

Jon Burlingame | The Film Music Society

More than 300 friends, family members and colleagues celebrated the life and career of composer Elmer Bernstein at a memorial service Wednesday night on the Paramount Pictures lot in Hollywood.

More than 300 friends, family members and colleagues celebrated the life and career of composer Elmer Bernstein at a memorial service Wednesday night on the Paramount Pictures lot in Hollywood.

Bernstein, the Oscar- and Emmy-winning composer of such classic film scores as To Kill a Mockingbird, The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape, died Aug. 18 after a long illness. He was 82.

The esteem in which he was held, and the affection felt for him, was indicated not only by the speakers but by the crowd of high-profile composers, lyricists, musicians, directors and other members of the Hollywood community in attendance.

Pianist Mike Lang opened the service with a solo-piano version of To Kill a Mockingbird, arranged by the composer in 1979 for his daughter Emilie. She then took to the podium and told the crowd that her father had, in the last days of his illness, said “I have lived a good life. I did everything I wanted to do.”

Emilie and her sister Elizabeth introduced director John Landis, who worked with Bernstein on eight projects including National Lampoon’s Animal House. Landis served as host for the event, reversing the inevitably downbeat mood by regaling the audience with amusing anecdotes – notably a prank they pulled on notorious German director Leni Riefenstahl while they were in Munich in 1985 scoring Spies Like Us.

ASCAP president Marilyn Bergman (who with her husband Alan collaborated with Bernstein on From Noon Till Three and other films) called Bernstein “a composer for all seasons… really a dramatist who crept into the fabric of every movie.”

She praised his leadership within the film-music community during the 1970s when, as president of the Composers and Lyricists Guild of America, he led a decade-long battle with the movie studios and TV networks for a greater share of music-ownership rights that would have benefited all creators of movie and TV music.

Peter Bernstein called his father “a fundamentalist in his own inner religion of creativity” and spoke of his “relentless optimism…. He deeply believed in the artistry of his profession.” He recalled watching, at the age of 9, his father conducting The Magnificent Seven score and marvelling at the dynamic qualities he brought to the recording.

Two of his father’s favorite words, he said, were “grace” and “joy.”

Lyricist Don Black recalled working with Bernstein on True Grit and the Broadway musical Merlin – as well as such “landmark motion pictures,” he added, tongue-in-cheek, as Where’s Jack?, The Midas Run and Cahill, U.S. Marshal.

“He had enough energy to illuminate a small town,” Black said. “I shall miss his warmth, his wit, his ready laugh, his boyish bounce – even his turtleneck sweaters.”

Producer Noel Pearson recounted stories from their 30-year friendship, including a pub encounter with Irish poet Christy Brown, whose life Pearson would later dramatize in the film My Left Foot – which, he said, Bernstein scored for free. “Elmer’s masterpieces have been completed,” he said, “and because of those masterpieces, he’ll always be with us.”

Gregory Bernstein told surprising and funny stories relating to his father’s “problem with authority figures,” including a memorable outing in which the fast-driving sports-car aficionado Bernstein eluded a police officer in the hills above Hollywood.

He spoke of his father’s “fearlessness” and the confidence that resulted in everything he did. “Failure was not part of his lexicon,” he said. He recalled Bernstein playing the piano with “such vigor, such energy, such force.”

Gregory also confirmed that his father had died of cancer, noting that just days after surgery, and later radiation treatments, Bernstein was active and back in the swing of life, piloting his boat and talking about future projects.

Director Martin Scorsese – whose film The Age of Innocence brought Bernstein an Oscar nomination – sent a personal video tribute, calling him “amazingly versatile,” whether working in a jazz idiom, a grand symphonic palette or with the intimacy of chamber music.

“He always understood the emotional arc of whatever picture we were working on,” Scorsese said. “He was the one composer who truly bridged the gap between the old Hollywood and the new. It was a pleasure and an honor for me to work with him,” he added. “He was a giant in the history of cinema. He will always be a giant.”

Composer James Newton Howard spoke of his “deep sense of connection” with Bernstein and said that the man’s “dignity and uncompromising professionalism” had influenced and inspired him. Bernstein’s music, he said, “exudes humanity.”

Far From Heaven director Todd Haynes, in remarks filled with emotion, said that his film had been “graced beyond belief” by Bernstein’s music. He said they had talked about collaborating on a film about Sigmund Freud.

Bernstein, he said, was “almost English in his old-world sophistication.” He spoke of the composer’s “ebullient warmth” and called him “a man of instinctive openness and elemental cool… an unrepentent liberal… a gentle mind and a solid heart.”

Pianist Lang executed a brilliantly jazzy version of The Man With the Golden Arm and, late in the program, a touching rendition of the theme for Far From Heaven. Guitarist Christopher Parkening, accompanied by pianist Paul Henning, played excerpts from the second movement of Bernstein’s guitar concerto.

A letter of condolence from composer John Barry was also read. The 95-minute program concluded with a montage of clips from 25 of his films along with photos from his life set to his own recent European performance of The Magnificent Seven; and a champagne toast to the maestro led by Bernstein’s manager Robert Urband.

Among others in attendance were directors Arthur Hiller and Bill Duke; composers Bruce Broughton, Johnny Mandel, Charles Bernstein, John Debney, Christopher Young, Ian Fraser, Fred Steiner, Dana Kaproff, William Ross, John Frizzell, James diPasquale, Richard Bellis, Mark Watters, Ray Colcord, Dan Foliart, Michael Isaacson, John Morgan and William Stromberg; orchestrator Jack Hayes; and film historian Leonard Maltin.

Reprint courtesy of The Film Music Society