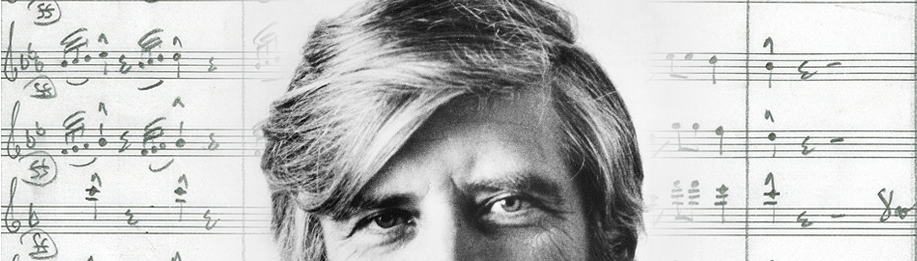

The Sound of Heaven

Elmer Bernstein Does It the Old-Fashioned Way, in Todd Haynes' Far From Heaven

Jeff Bond | Film Score Monthly

Far From Heaven takes place in a world of happy homemakers, successful TV marketing executives and chirpy, well-adjusted siblings-in short, it takes place in the ’50s, an era when black people knew their place and homosexuality was something you just didn’t talk about. Director Todd Haynes’ previous feature was Safe, with Julianne Moore as a Los Angeles resident whose body begins to rebel against what it perceives as a toxic environment. In Far From Heaven Moore’s character is also in conflict with her environment, but this time the conflict is social: When the happily married woman discovers her husband (Dennis Quaid) is involved in a homosexual affair, she finds herself increasingly closed off from the local community and discovers that her only confidant is her African American gardener (Dennis Haysbert).

Far From Heaven isn’t simply set in the ’50s. Director Todd Haynes’ intention was to film his story using the cinematic language, performance style and dialogue from movies of the period, in effect attempting to tell a story the way it would have been told had this subject matter been approachable at that time. But the heroine, her husband and the people in their social environs don’t even have the vocabulary to discuss the implications of their predicament. All of this made the choice of composer for the movie crucial: The score to Far From Heaven had to be one that might have been written for a ’50s movie, but it also had to address emotions and situations that a ’50s film could never have touched.

Out of the Past

Bernstein acknowledges the difficulty that Far From Heaven may hold for audiences for whom the subject of homosexuality and race are far from forbidden. “It’s very hard because first of all you’re looking at characters at a remove of 40 years or so,” the composer says. “It was a different time, they were different people, they acted differently. And having lived through that period I can tell you that it was very faithful to the period.” Bernstein points out that the subject of homosexuality couldn’t even be discussed in a film of the period, a situation which plays into one of Far From Heaven’s most powerful scenes, in which Moore’s character and her husband attempt-utterly without success-to discuss the man’s homosexual liaison after his wife stumbles in on it. “It was considered to be an illness,” Bernstein explains. “They hustled a homosexual off to the psychiatrist right away to get cured.”

Bernstein’s uniquely American musical voice helps set the stage for the film as it establishes a homey, comforting vision of 1950s America, only to see Dennis Quaid’s character drift into the distinctly “un-American” environment of a gay bar. In keeping with the film’s template of ’50s melodrama, Bernstein’s score had to establish an unsettling mood for this sequence. “Todd Haynes said his feeling about all the gay stuff at the beginning was that he wanted it dealt with in terms of 1950s,” Bernstein says. “In other words, he wanted the music to be slightly off-center like something’s wrong, because that’s what gay life was like in the ’50s-it was something wrong. I thought that was rather interesting; I don’t think I would have gone that far on my own.”

Bernstein’s score is unusually active throughout the film, engaging in genuine psychological scoring and indicating thoughts and feelings the characters are often unable to express. The composer was even able to write a relatively sweeping title theme that included a dramatic cymbal crash for the film’s stylized opening. “At the very beginning in the main title music, you know that we’re going to get into a drama with problems. The music is not happy. It’s not tragic but you just know that there are problems,” Bernstein explains. As Moore’s character becomes increasingly alienated from her husband and finds herself unable to express what she’s going through to her friends, she begins to confide in her African American gardener and develops a friendship with him. When the two go for a walk in the woods outside of town, Bernstein introduces a gorgeous, lyrical theme that is used psychologically later on as Moore’s character finds herself thinking of the man. “In that big outdoor scene with the gardener, that’s a happy scene, and I kept the music kind of sunny, the only sunny thing in the film really, because that’s her haven at that moment,” Bernstein says.

Far From Heaven’s final scene between Moore and Haysbert is played entirely without dialogue, allowing Bernstein’s music to carry the bulk of the sequence’s emotion. “For me, Safe and this film are bookends in a curious sort of way,” Bernstein says of the film’s ending. “Safe is a film about a woman who is not going to make it. She goes into that igloo house at the end of Safe and you somehow feel that she is never going to come out. In this film, even though she loses both men in her life, I have the feeling she’s going to go on with her life. That’s why I called that cue ‘Beginnings.’ In this film I felt like she’s going to have a chance now.”

Reconnecting With His Roots

Bernstein points out Far From Heaven as a welcome change of pace in the current environment of film scoring in which composers are often discouraged from putting much personality into their work-a real problem for musicians of Bernstein’s generation who have such an immediately recognizable style. “Let’s face it, nobody wants it,” Bernstein says. “The kind of work that composers like myself do, we’re kind of an annoyance now to most people. Not all of them, but so many of them really want somebody who can write connective music that kind of lies beneath the pop music in the picture. There are great exceptions of course. This year John Williams on Minority Report really did an interesting score, and Thomas Newman on Road to Perdition I thought was brilliant.” Bernstein acknowledges that after 200 scoring assignments, he’s had to work on films that failed to inspire him, but he still sees a challenge in the work. “I kind of wait for the film to tell me something and find out what’s at the core of the film and what can I do for it and what can I do to help it. That’s what keeps me going.”

Success All Around

So far Bernstein is getting some of the best reviews of his career for Far From Heaven, and he’s not doing badly on other fronts, either. His Guitar Concerto was recently premiered at the Hollywood Bowl and was highly praised by the Los Angeles Times, a newspaper known for its withering reviews of Hollywood composers who dare to enter the concert realm. Bernstein thinks there’s a simple reason for the praise. “Even in the Concerto, I have not said, ‘Oh boy, now I’m going to assume my concert hall personality and become a completely different person.’ Musically, the Concerto is me-not me who is now trying to write Schoenberg.”

One of the biggest fans of Bernstein’s Far From Heaven score is the film’s director, who held a clear enthusiasm for what the composer was doing at the film’s scoring sessions. Haynes acknowledges that the Far From Heaven score could have fit neatly into an actual film of the period, although he says he never demanded that Bernstein approach the film in that way. “We never really said, ‘Oh, let it be really big and splashy,’ or anything like that, but in some ways it is bigger and splashier than I anticipated,” he says. “But there’s something incredibly pure about it, and there’s something that will work so well with what I was doing in the film style. We really are completely following the rules of narrative and visual style of that period, but it’s never meant to be a spoof, it’s never meant to be ironic, and that’s hard for today’s audiences to understand. That will be the trick of how to promote this film, because it’s hard for anyone to enter into this realm today without it being tongue-in-cheek, and it’s really not-it’s really honest about these characters and what they’re going through, and I think it’s reflected both in the score and the film style.”

Jeff Bond is FSM’s senior editor; you can contact him via jbond@filmscoremonthly.com

Reprint Courtesy of Film Score Monthly