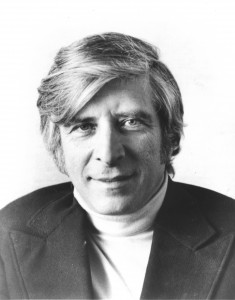

Elmer Bernstein’s life could have been set to music, and for many, it was. Affable, fearless and genuine, the man behind the music that has already surpassed the test of time was a man with a golden touch. His contribution to film music is celebrated. His contribution to new generations of aspiring musicians continues. His exuberance for life is still felt.

Elmer Bernstein’s life could have been set to music, and for many, it was. Affable, fearless and genuine, the man behind the music that has already surpassed the test of time was a man with a golden touch. His contribution to film music is celebrated. His contribution to new generations of aspiring musicians continues. His exuberance for life is still felt.

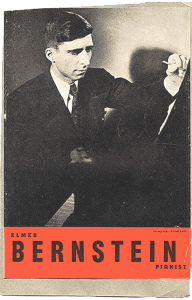

In the history of film music, Elmer Bernstein (1922-2004) is among the iconic and the legendary. With a career that spanned an unparalleled 5 decades, he composed more than 150 original movie scores and nearly 80 for television, creating some of the most recognizable and memorable themes in Hollywood history: the driving jazz of The Man With the Golden Arm, the rousing Western anthem of The Magnificent Seven, the lyrical and quietly moving music of To Kill a Mockingbird, and the jaunty, thumb-nosing march of The Great Escape. His impact is still felt, and his presence still missed, by moviemakers and moviegoers alike.

The Early Years

Born in New York of Ukrainian immigrant parents on April 4, 1922, he was originally destined for a career in classical music. As a young pianist, he gave his first concert at the age of 15 in New York’s Steinway Hall. Encouraged by Aaron Copland, he undertook composition studies with several important teachers including Roger Sessions and Stefan Wolpe.

Elmer Bernstein talks about his childhood, piano studies, and how his musical improvisations led him to Aaron Copland

World War II intervened, and the young composer got his first taste of writing music for drama by working on radio shows in the Army Air Force. When the war ended, he returned to the highbrow world of classical piano, but continued to dabble in radio scoring for the United Nations and such legendary radio dramatists as Norman Corwin. ??His break came in 1950 when writer Millard Lampell, an old service buddy, convinced producer Sidney Buchman to hire the novice composer on a football movie he had written. Saturday’s Hero was made for Columbia, which released the film in 1951.

Elmer Bernstein explains how he got his first film assignment through a combination of luck and timing.

The next year, his music for the Joan Crawford thriller, Sudden Fear, attracted critical attention. However, by 1953, he found himself virtually unemployable, reduced to doing B-movies like Robot Monster and Cat Women of the Moon. He soon learned that for his involvement with left-wing causes, he had been “graylisted”; and although he was never a member of the Communist Party, his having written music reviews for the “red” paper Daily Worker in the late ’40s, and having been associated with known party members, was enough to make the list.

Elmer Bernstein discusses being “graylisted” in the McCarthy Era of the 1950s

A Career is Born

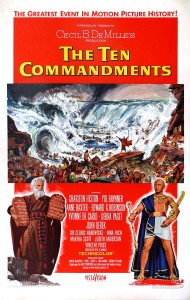

Bernstein wound up working as a rehearsal pianist for the ballet sequences in the film version of Oklahoma! and working with Danny Kaye’s wife, Sylvia Fine, jotting down her tunes for The Court Jester at Paramount. A studio music executive, taking pity on Bernstein, introduced him to Cecil B. De Mille, who was then shooting The Ten Commandments and who needed ancient-sounding music for dances in the film. Eventually, Victor Young—who had originally been signed to write the dramatic music—dropped out due to health reasons, and DeMille replaced the ailing composer with Bernstein.

“‘Mr. Bernstein,’ DeMille said in the great voice, ‘do you think that you can do for ancient Egyptian music what Puccini did for Japanese music in ‘Madame Butterfly?” And I thought about that…”

Elmer Bernstein remembers his first meeting with Cecil B. DeMille and his big break on “The Ten Commandments”

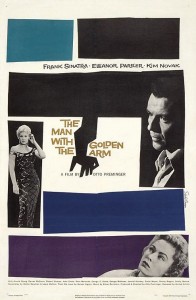

During the year and a half that he was working on The Ten Commandments, he also composed the groundbreaking jazz score for The Man With the Golden Arm for director Otto Preminger.

“I knew that it was a seminal film in the sense of the particular way jazz was used in the film. Other people used jazz in films before, but never so thorough-going or so violently.”

Elmer Bernstein discusses writing a jazz score for “The Man With the Golden Arm”

The soundtrack album for Man With the Golden Arm shot to No. 2 on the Billboard album charts in 1956, becoming one of the first hit movie soundtracks. These scores catapulted Bernstein onto the “A” list of Hollywood composers and wiped out any more talk of “graylisting.” Golden Arm won him his first Oscar nomination and launched a series of jazz-oriented Bernstein scores, including Sweet Smell of Success, The Rat Race, TV’s Staccato and Walk on the Wild Side.

The jazz scores, plus the spate of Westerns and dramas that would dominate the composer’s work throughout the ’60s, helped to solidify his reputation as a master of musical Americana. The robust, exciting music of The Magnificent Seven brought another Oscar nomination and offers to do Westerns of all kinds, including seven John Wayne films, among them The Comancheros (1961), True Grit (1969) and The Shootist (1976).

“I really loved the Westerns,” said Bernstein. “They were fun to do, because they addressed themselves to a particular kind of Americana which started with Aaron [Copland]. Also, in my early years, I spent a lot of time with American folk music. It was like discovering a magic world. I think a lot of that stuck with me; it was part of my musical heritage.”

Elmer Bernstein talks about writing the music for “The Magnificent Seven”

Meanwhile, Bernstein’s close relationship with producer Alan J. Pakula and director Robert Mulligan led to one of his most memorable scores, and for one of the finest American movies ever made: To Kill a Mockingbird. The familiar classic about racial prejudice, set in a small town in the depression-ridden South, won Oscars for Gregory Peck and screenwriter Horton Foote in 1962, and a nomination for Bernstein. His understated music, composed for a chamber-sized ensemble rather than the more traditional full orchestra, quickly became a new model for film composers.

“After the longest period of time, I suddenly realized—it came to me that what was going on here was a series of real-world adult problems, but seen through the eyes of children. That was the key thing.”

Elmer Bernstein discusses his music for “To Kill a Mockingbird”

Bernstein’s versatility as a composer was again demonstrated when, the very next year, he created another classic with the theme for The Great Escape, a fact-based World War II adventure film about Allied soldiers who plan an elaborate escape from a prisoner-of-war camp.

“John [Sturges], who directed it, had a very unique way of working: He didn’t care about your reading the script. … You would spend a morning with him in the office and he would tell you the story. He was the most magnificent story-teller.”

Elmer Bernstein talks about scoring “The Great Escape”

One of Bernstein’s most enduring compositions that’s still in use today (although rarely credited to him) is the fanfare for the National Geographic specials of the 1960s, ’70s and beyond:

It was also in the ‘60s that Bernstein produced what may have been the best of his five scores for director George Roy Hill: United Artists’ production of James Michener’s epic historical novel, Hawaii (1966). A labor of love and a personal favorite, Bernstein’s soaring, symphonic tapestry of grand proportions earned him an Oscar nomination and the Golden Globe Award.

“I did a lot of interesting research for that score. None of it was really useful musically. … Just soaking in all that Hawaiian magic and mystic was I think a good thing.”

Elmer Bernstein discusses his epic score for “Hawaii”

Beyond Film

Elmer Bernstein was more than a composer—he was an explorer—always intrigued by the potential of creative collaborations and applying his musical dexterity to different media. Trips to Broadway earned him Tony nominations for best musical score in 1967 for How Now Dow Jones and in 1983 for Merlin. One of his songs for How Now Dow Jones, “Step to the Rear,” even became a hit, as sung by Tony Roberts:

Throughout his career, Bernstein took on a number of leadership roles, including stints as vice president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, president of the Young Musicians Foundation, president of The Film Music Society and, most significantly, a decade-long tenure as president of the now-defunct Composers and Lyricists Guild of America during the 1970s—where he fought a lengthy, expensive and ultimately futile battle against the studios in an effort to restore composers’ rights to their music for movies and TV.

Elmer Bernstein on serving the Hollywood music community

He was also avidly interested in educating young people: giving back to his childhood school, Walden, in New York City; helping to establish the Young Musicians Foundation; and regularly conducting the Valley Symphony Orchestra. Determined to help promote the great legacy of Hollywood film music, Bernstein invested his own money in the “Film Music Collection,” conducting a series of recordings of classic scores and issuing a quarterly journal on the subject.

A Funny Thing Happened… And Then Another

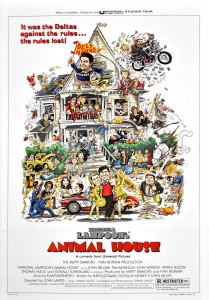

Bernstein’s career took a surprising turn in 1978, thanks to a call from his son Peter’s old school chum, John Landis. Landis, then 27 and a film director, asked Bernstein to score his raucous college comedy Animal House starring John Belushi.

“When John [Landis] showed me the film, I said, ‘Why me, John?’ [laughing]

“John said, ‘Well I have an idea. … How about you do a score that has nothing to do with comedy?”

Elmer Bernstein talks about scoring comedies, including “Animal House”

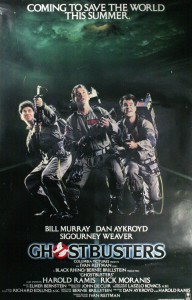

Almost overnight, Bernstein became Hollywood’s go-to composer for funny movies, and for the next decade he was largely typecast in that role. Airplane! came in 1980, followed over the next four years by the Saturday Night Live alumni movies, The Blues Brothers (John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd), Stripes (Bill Murray), and Ghostbusters (Dan Aykroyd and Bill Murray). For his 1983 comedy, Trading Places, starring Eddie Murphy and Dan Aykroyd, Landis talked Bernstein into crafting a classical score from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, for which he would receive an Oscar nomination for Best Adaptation Score.

But Seriously…

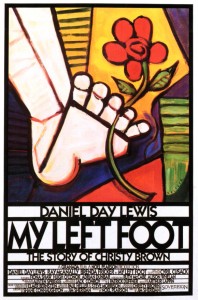

In Landis’ ¡Three Amigos!, with Steve Martin and Chevy Chase, Bernstein was encouraged to send up his own classic Western style. He eventually tired of comedies, however, and shifted back to smaller, more finely crafted dramas, such as Noel Pearson’s critically acclaimed My Left Foot (1989), starring Daniel Day Lewis.

EB talks about Noel Pearson and “My Left Foot”

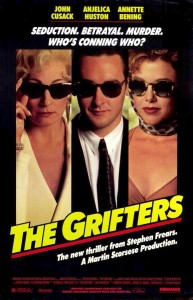

The Grifters marked Bernstein’s first work with celebrated filmmaker Martin Scorsese, whose role was that of producer on the con-artist film starring Anjelica Huston, John Cusack and Annette Bening. In part, Bernstein was hired for his legendary jazz scores of the ’50s and early ’60s. Director Stephen Frears, however, failed to apply Bernstein’s score in the way the composer intended:

“There were about 33 pieces of music in the film. … When [Director Stephen Frears] got through with it, only three of the pieces remained in the spots for which they were originally written.”

Elmer Bernstein talks about the music for “The Grifters”

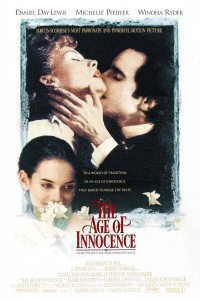

For Scorsese as director, Bernstein adapted Bernard Herrmann’s original Cape Fear score for the 1991 remake; provided the musical atmosphere for Bringing Out the Dead; and wrote a stunning score, although ultimately unused, for Gangs of New York. He received a 1993 Oscar nomination for the elegant music of Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence.

“[Scorsese] loves music. He understands very, very acutely what music does in a film. … On the Age of Innocence we went a step further….”

Elmer Bernstein discusses working with Martin Scorsese and “The Age of Innocence”

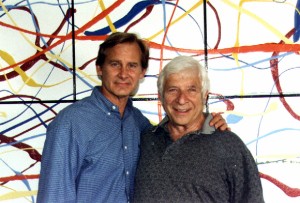

In person, Bernstein was warm and approachable, thoughtful and fun-loving; and despite 50 years of being “in the biz,” he was surprisingly optimistic. Actor Edward Norton, who hired Bernstein for his first film as a director (Keeping the Faith, 2000), said: “He is one of the most vibrant people I’ve worked with. It’s his very youthful enthusiasm that makes it so invigorating to work with him. He brings the full depth of his classical training and classic Hollywood experience to the table—but he brings with it the energy of a 28-year-old.”

The Spirit of Exploration

The energy Edward Norton referred to had few limitations, if any, and Bernstein eagerly embraced different genres and applications of music-making: of note, his scores for the many short films of husband-and-wife team Charles and Ray Eames, beginning in the early 1950s.

Elmer Bernstein talks about working on short films with Charles and Ray Eames

Towards the end of his life, Bernstein returned to his classical roots, composing a well-received guitar concerto for celebrated guitarist Christopher Parkening.

“I found writing a long piece for the guitar really daunting. Because I’m not a guitarist. … Then Chris [Parkening] said something to me that really freed me up a lot….”

Elmer Bernstein discusses composing his guitar concerto

Bernstein’s last major film score was for the critically praised, Todd Haynes-directed drama, Far From Heaven, starring Julianne Moore and Dennis Haysbert. It earned him his final Academy Award nomination in 2002.

“I regard Far From Heaven as a late-life gift. … I thought to myself: I don’t know where this film will go, but there’s a wonderful open space to write music I love writing, but never get a chance to do anymore.”

Elmer Bernstein talks about scoring “Far From Heaven,” his last major film

50 Years of Making a Difference

Asked about surviving the changes in films and filmmaking over the years, Bernstein said, “It doesn’t feel like 50 years.” He acknowledged, however, that versatility was a big factor in his longevity—scoring a historical epic one month, tackling a western the next, then an intimate drama. “I think I have demonstrated an enthusiasm for change, and that’s fairly infectious,” he added. “I would hope that some of the energy and joy that exists in some of the work would communicate years and years from now.”

He reflected on his life and work in a 2001 interview with journalist and author Jon Burlingame:

Elmer Bernstein reflects on his life and career

On August 18, 2004, surrounded by family at his home in Ojai, California, Elmer Bernstein lost his battle with cancer. He was 82. His memorial service, held in October at Paramount Pictures, saw an attendance of over 300 friends, family members, and colleagues, but he was mourned by millions. The world had lost one of its most celebrated and beloved composers, but the music lives on, for new generations, in live concerts, film, television, and the internet.

—By Jon Burlingame